Saka language

In today's world, Saka language has become a topic of great relevance and interest. Whether due to its impact on society, its historical relevance or simply its importance in daily life, Saka language has captured the attention of millions of people around the world. It is a topic that has generated debate, controversy and reflection, and has inspired individuals and communities to take action. In this article, we will explore in depth the meaning and importance of Saka language, as well as its influence on different aspects of life.fromJson=make me a long generic introductory paragraph to an article from an article

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2025) |

| Saka | |

|---|---|

| Khotanese, Tumshuqese | |

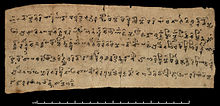

Khotanese animal zodiac BLI6 OR11252 1R2 1 | |

| Native to | Kingdom of Khotan, Tumshuq, Murtuq, Shule Kingdom,[1] and Indo-Scythian Kingdom |

| Region | Tarim Basin (Xinjiang, China) |

| Ethnicity | Saka |

| Era | 100 BC – 1,000 AD developed into Wakhi[2] |

| Dialects |

|

| Brahmi, Kharosthi | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | kho |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:kho – Khotanesextq – Tumshuqese |

kho (Khotanese) | |

xtq (Tumshuqese) | |

| Glottolog | saka1298 |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Saka, or Sakan, was a variety of Eastern Iranian languages, attested from the ancient Buddhist kingdoms of Khotan, Kashgar and Tumshuq in the Tarim Basin, in what is now southern Xinjiang, China. It is a Middle Iranian language.[3] The two kingdoms differed in dialect, their speech known as Khotanese and Tumshuqese.

The Saka rulers of the western regions of the Indian subcontinent, such as the Indo-Scythians and Western Satraps, are traditionally assumed to have spoken practically the same language.[4] This has however been questioned by more recent research.[5]

Documents on wood and paper were written in modified Brahmi script with the addition of extra characters over time and unusual conjuncts such as ys for z.[6] The documents date from the fourth to the eleventh century. Tumshuqese was more archaic than Khotanese,[7] but it is much less understood because it appears in fewer manuscripts compared to Khotanese. The Khotanese dialect is believed to share features with the modern Wakhi and Pashto.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14] Saka was known as "Hvatanai" (from which the name Khotan) in contemporary documents.[15] Many Prakrit terms were borrowed from Khotanese into the Tocharian languages.

Classification

Khotanese and Tumshuqese are closely related Eastern Iranian languages.[16]

The unusual phonological development of Proto-Iranian *ću̯ to Khotanese śś sets the latter apart from most other Iranian languages (which usually have sp or a product thereof). Similarities with Sogdian exist but could be due to parallel developments or areal features.[17]

History

The two known dialects of Saka are associated with a movement of the Scythians. No invasion of the region is recorded in Chinese records and one theory is that two tribes of the Saka, speaking the two dialects, settled in the region in about 200 BC before the Chinese accounts commence.[18]

Michaël Peyrot (2018) rejects a direct connection with the "Saka" (塞) of the Chinese Hanshu, who are recorded as having immigrated in the 2nd century BC to areas further west in Xinjiang, and instead connects Khotanese and Tumshuqese to the long-established Aqtala culture (also Aketala, in pinyin) which developed since ca. 1000 BC in the region.[19]

The Khotanese dialect is attested in texts between the 7th and 10th centuries, though some fragments are dated to the 5th and 6th centuries. The far more limited material in the Tumshuqese dialect cannot be dated with precision, but most of it is thought to date to the late 7th or the 8th century.[20][21]

The Saka language became extinct after invading Turkic Muslims conquered the Kingdom of Khotan in the Islamicisation and Turkicisation of Xinjiang.

In the 11th century, it was remarked by Mahmud al-Kashgari that the people of Khotan still had their own language and script and did not know Turkic well.[22][23] According to Kashgari some non-Turkic languages like the Kanchaki and Sogdian were still used in some areas.[24] It is believed that the Saka language group was what Kanchaki belonged to.[25] It is believed that the Tarim Basin became linguistically Turkified by the end of the 11th century.[26]

Old Khotanese phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal/ | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | Voiceless | Unaspirated | p /p/ | tt, t /t/ | ṭ /ʈ/ | k /k/ | (t, g )[a] | |

| Aspirated | ph /pʰ/ | th /tʰ/ | ṭh /ʈʰ/ | kh /kʰ/ | ||||

| Voiced | b /b/ | d /d/ | ḍ /ɖ/ | gg /ɡ/ | ||||

| Affricate | Voiceless | Unaspirated | tc /ts/ | kṣ /ʈʂ/ | c, ky /tʃ/ | |||

| Aspirated | ts /tsʰ/ | ch /tʃʰ/ | ||||||

| Voiced | js /dz/ | j, gy /dʒ/ | ||||||

| Fricative | Non-Sibilant | t /ð/ (later > ʔ) | g /ɣ/ (later > ʔ) | |||||

| Sibilant | Voiceless | s /s/ | ṣṣ, ṣ /ʂ/ | śś, ś /ʃ/ | h /h/ | |||

| Voiced | ys /z/ | ṣ /ʐ/ | ś /ʒ/ | |||||

| Nasal | m /m/ | n, ṃ, ṅ /n/ | ṇ /ɳ/ | ñ /ɲ/ | ||||

| Approximant | Central | v /w/ hv /wʰ/, /hʷ/ |

rr, r /ɹ/ | r /ɻ/ | y /j/ | |||

| Lateral | l /l/ | |||||||

Vowels

| Khotanese Transliteration[30] |

IPA Phonemic | IPA Phonetic |

|---|---|---|

| a | /a/ | |

| ā | /a:/ | |

| i | /i/ | |

| ī | /i:/ | |

| u | /u/ | |

| ū | /u:/ | |

| ä | /ə/ | |

| e | /e:/[b] | [c] |

| o | /o:/[b] | [c] |

| ai | /ai̯/ | |

| au | /au̯/ | |

| ei | /ae̯/ |

Sound changes

Khotanese was characterized by pervasive lenition, developments of retroflexes and voiceless aspirated consonants.[31]

- Changes shared in common Sakan

- *ć, *j́ → s, ys, but *ćw, *j́w → śś, ś

- *ft, *xt → *βd, *ɣd

- Lenition of *b, *d, and *g → *β, ð, ɣ when initially or after vowels or *r

- Nasals + voiceless consonants → nasals + voiced consonants (*mp, *nt, *nč, *nk → *mb, *nd, *nj, *ng)

- *ər (syllabic consonant) → *ur after labials *m, *p, *b, *β; then *ir or *ar elsewhere

- *rn, *rm → rr

- *sr → ṣ

- *č, *ǰ → tc, js

- Changes shared in East Sakan

- Nasals + voiced consonants → geminate nasals (*mb, *nd → *mm, *nn, but *ng remained)

- Questionable umlaut of *a into i and u before syllables with *i and *u, respectively (*masita → *misita → mista ~ mästa "big")

- Lenition of *p, *t, *č, and *k → b, d, ǰ, and g after vowels or *r

- *f, *x → *β, *ɣ before consonants

- *ɣ → *i̯ between vowels a, i and a consonant (*daxsa- → *daɣsa- → *daisa- → dīs- "to burn")

- *β → w; *ð, *ɣ → ∅ after vowels

- *rð → l

- *f, *θ, *x → *h after vowels

- *w, *j → *β, *ʝ initially

- *f, *θ, *x → *β, ð, ɣ initially before *r (θrayah → ðrayi → drai "three")

- Lengthening of stressed vowels before clusters *rC and *ST (sibilants + dentals) (*sarta → *sārta → sāḍa "cold", *astaka → āstaa "bone" but not *aštā́ → haṣṭā "eight").

- Compensatory lengthening of vowels, before clusters containing non-sibilant fricatives and *r (*puhri → pūrä "son", darɣa → dārä "long"), however, -ir- and -ur- from earlier *ər were unaffected (*mərɣa- → mura- "fowl").

- Reduction of internal unstressed short and long vowels (*hámānaka → *haman

aka → hamaṅgä) - *uw → u

- *β, ð, ʝ, ɣ > b, d, ɟ, g initially

- *f, *θ, *x → ph, th, kh (remaining instances)

- *rth → ṭh; *rt, *rd → ḍ

- Lenition of b, d, g (from earlier voiceless consonants) → β (→ w), ð, ɣ after vowels or *r

- ḍ also phonetically became ḷ or ṛ in this position.

- Palatalization of certain consonants:

| Earlier | Later |

|---|---|

| *ky | c, ky |

| *gy | j, gy |

| *khy | ch |

| *tcy | c |

| *jsy | j |

| *tsy | ch |

| *ny | ñ, ny |

| *sy | śś |

| *ysy | ś |

| *st, *ṣṭ | śt, śc |

Texts

Other than an inscription from Issyk kurgan that has been tentatively identified as Khotanese (although written in Kharosthi), all of the surviving documents originate from Khotan or Tumshuq. Khotanese is attested from over 2,300 texts[32] preserved among the Dunhuang manuscripts, as opposed to just 15 texts[33] in Tumshuqese. These were deciphered by Harold Walter Bailey.[34] The earliest texts, from the fourth century, are mostly religious documents. There were several viharas in the Kingdom of Khotan and Buddhist translations are common at all periods of the documents. There are many reports to the royal court (called haṣḍa aurāsa) which are of historical importance, as well as private documents. An example of a document is Or.6400/2.3.

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Mallory, J. P. (2010). "Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Expedition. Vol. 52, no. 3. Penn Museum. pp. 44–53. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Parpola, Asko; Koskikallio, Petteri, eds. (2001). Early contacts between Uralic and Indo-European: linguistic and archaeological considerations: papers presented at an international symposium held at the Tvärminne Research Station of the University of Helsinki, 8-10 January, 1999. Suomalais-ugrilaisen Seuran toimituksia. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. ISBN 978-952-5150-59-9.

- ^ "Saka Language". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ^ Diringer, David (1953) . The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind (Second and revised ed.). London: Hutchinson's Scientific and Technical Publications. p. 350.

- ^ Michaël Peyrot (2018). "Tocharian B etswe 'mule' and Eastern East Iranian". Farnah. Indo-Iranian and Indo-European Studies in Honor of Sasha Lubotsky. Ann Arbor, N.Y.: Beech Stave Press. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

In sum, the evidence that the Saka language is Khotanese or an earlier form of it is weak. Many of the features are found in other languages as well, and it is known from other sources that non-Khotanese Iranians found their way to northern India. In any case, the large number of Indic elements in Khotanese is no proof "daß das 'Nordarisch' sprechende Volk längere Zeit auf indischem Boden saß" (Lüders 1913), since there is ample evidence that instead speakers of Middle Indian migrated into the Tarim Basin.

- ^ Bailey, H. W. (1970). "Saka Studies: The Ancient Kingdom of Khotan". Iran. 8: 65–72. doi:10.2307/4299633. JSTOR 4299633.

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Paris: UNESCO. 1992. p. 283. ISBN 92-3-103211-9.

- ^ Frye, R.N. (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. p. 192. ISBN 9783406093975.

hese western Saka he distinguishes from eastern Saka who moved south through the Kashgar-Tashkurgan-Gilgit-Swat route to the plains of the sub-continent of India. This would account for the existence of the ancient Khotanese-Saka speakers, documents of whom have been found in western Sinkiang, and the modern Wakhi language of Wakhan in Afghanistan, another modern branch of descendants of Saka speakers parallel to the Ossetes in the west.

- ^ Bailey, H.W. (1982). The culture of the Sakas in ancient Iranian Khotan. Caravan Books. pp. 7–10.

It is noteworthy that the Wakhi language of Wakhan has features, phonetics, and vocabulary the nearest of Iranian dialects to Khotan Saka.

- ^ Carpelan, C.; Parpola, A.; Koskikallio, P. (2001). "Early Contacts Between Uralic and Indo-European: Linguistic and Archaeological Considerations: Papers Presented at an International Symposium Held at the Tvärminne Research Station of the University of Helsinki, 8–10 January, 1999". Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. 242: 136.

...descendants of these languages survive now only in the Ossete language of the Caucasus and the Wakhi language of the Pamirs, the latter related to the Saka once spoken in Khotan.

- ^ "Encolypedia Iranica, AFGHANISTAN vi. Paṣ̌tō".

It is, however, possible that the original home of Paṣ̌tō may have been in Badaḵšān, somewhere between Munǰī and Sangl. and Shugh., with some contact with a Saka dialect akin to Khotanese.

- ^ Indo-Iranica. Kolkata, India: Iran Society. 1946. pp. 173–174.

... and their language is most closely related to on the one hand with Saka on the other with Munji-Yidgha

- ^ Bečka, Jiří (1969). A Study in Pashto Stress. Academia. p. 32.

Pashto in its origin, is probably a Saka dialect.

- ^ Cheung, Jonny (2007). Etymological Dictionary of the Iranian Verb. (Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series).

- ^ Bailey, H. W. (1939). "The Rāma Story in Khotanese". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 59 (4): 460–468. doi:10.2307/594480. JSTOR 594480.

- ^ Emmerick, Ronald (2009). "Khotanese and Tumshuqese". In Windfuhr, Gernot (ed.). The Iranian Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 377–415.

- ^ Michaël Peyrot (2018). "Tocharian B etswe 'mule' and Eastern East Iranian". Farnah. Indo-Iranian and Indo-European Studies in Honor of Sasha Lubotsky. Ann Arbor, N.Y.: Beech Stave Press. pp. 270–283. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Bailey, H. W. (1970). "Saka Studies: The Ancient Kingdom of Khotan". Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 8 (1): 68. doi:10.2307/4299633. JSTOR 4299633.

- ^ Michaël Peyrot (2018). "Tocharian B etswe 'mule' and Eastern East Iranian". Farnah. Indo-Iranian and Indo-European Studies in Honor of Sasha Lubotsky. Ann Arbor, N.Y.: Beech Stave Press. pp. 270–283. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Emmerick, Ronald E. (2009). "7. Khotanese and Tumshuqese". In Windfuhr, Gernot (ed.). The Iranian Languages. Routledge. pp. 377–415. ISBN 978-1-135-79704-1.

- ^ "Saka language" at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Kocaoğlu, Timur (2004). "Diwanu Lugatı't-Turk and Contemporary Linguistics" (PDF). MANAS Journal of Turkic Civilization Studies. 1: 165–169. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-05-19. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ^ Levi, Scott Cameron; Sela, Ron, eds. (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- ^ Levi, Scott Cameron; Sela, Ron, eds. (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Crossroads of Civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO Publishing. 1996. pp. 283–. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- ^ Akiner, Shirin, ed. (2013). Cultural Change and Continuity in Central Asia. London: Routledge. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-136-15034-0.

- ^ Hitch, Douglas (2016). The Old Khotanese Metanalysis (Thesis). Harvard University.

- ^ Emmerick, R. E.; Pulleyblank, E. G. (1993). A Chinese text in Central Asian Brahmi script: new evidence for the pronunciation of Late Middle Chinese and Khotanese. Roma: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

- ^ Maggi, M. (2022). "Some remarks on the history of the Khotanese orthography and the Brāhmī script in Khotan". Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University. 25: 149–172.

- ^ Hitch, Douglas (2016). The Old Khotanese Metanalysis (Thesis). Harvard University.

- ^ Kümmel, M. J. (2016). "Einführung ins Ostmitteliranische".

- ^ Wilson, Lee (2015-01-26). "Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Khotanese Script" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-14. Retrieved 2019-05-21 – via unicode.org.

- ^ "Brāhmī". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2019-05-17. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- ^ "Bailey, Harold Walter". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2021-08-14. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

Sources

- "International Dunhuang Project". Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- Bailey, H. W. (1944). "A Turkish-Khotanese Vocabulary" (PDF). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 11 (2): 290–296. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00072475. JSTOR 609315. S2CID 163021887. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-15.

Further reading

- ""Prothetic H-" in Khotanese and the Reconstruction of Proto-Iranic" (PDF). Martin Kümmel. Script and Reconstruction in Linguistic History―Univerzita Karlova v Praze, March 2020.

- Bailey, H. W. (1979). Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge University Press.

- "Iranian Languages". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Emmerick, R. E.; Pulleyblank, E. G. (1993). A Chinese text in Central Asian Brahmi script: new evidence for the pronunciation of Late Middle Chinese and Khotanese. Roma: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. (On connections between Chinese and Khotanese, such as loan words and pronunciations)

- Litvinsky, Boris Abramovich; Vorobyova-Desyatovskaya, M. I. (1999). "Religions and Religious Movements". History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 421–448. ISBN 8120815408.

- Maggi, M. (2022). "Some remarks on the history of the Khotanese orthography and the Brāhmī script in Khotan". Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University. 25: 149–172.