Quapaw language

In today's world, Quapaw language remains a topic of great importance and interest to a wide public. Its relevance transcends borders and generations, and its impact has been felt in various spheres of society. From its emergence to the present, Quapaw language has been the subject of debate, analysis and reflection, constantly generating new perspectives and approaches on its meaning and influence. In this article, we will explore the many facets of Quapaw language, examining its evolution over time and its relevance in the contemporary context. Through a detailed analysis and a critical look, we will seek to delve deeper into the meaning of Quapaw language and its impact on our lives, offering a comprehensive vision that allows us to understand its importance in today's world.

| Quapaw | |

|---|---|

| Arkansas, O-gah-pah, Okáxpa | |

| Native to | United States |

| Region | Arkansas, Oklahoma |

| Ethnicity | 160 Quapaw (2000 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 0 (2022)[2] |

Siouan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | qua |

| Glottolog | quap1242 |

| ELP | Quapaw |

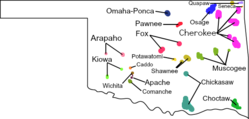

Map showing the distribution of Oklahoma Indian languages | |

Quapaw, or Arkansas, is a Siouan language of the Quapaw people, originally from a region in present-day Arkansas. It is now spoken in Oklahoma.

It is similar to the other Dhegihan languages: Kansa, Omaha, Osage and Ponca.

Written documentation

The Quapaw language is well-documented in field notes and publications from many individuals including by George Izard in 1827, by Lewis F. Hadly in 1882, from 19th-century linguist James Owen Dorsey, in 1940 by Frank Thomas Siebert, and, in the 1970s by linguist Robert Rankin.[3]

The Quapaw language does not conform well to English language phonetics, and a writing system for the language has not been formally adopted. All of the existing source material on the language utilizes different writing systems, making reading and understanding the language difficult for the novice learner. To address this issue, an online dictionary of the Quapaw language is being compiled which incorporates all of the existing source material known to exist into one document using a version of the International Phonetic Alphabet which has been adapted for Siouan languages.[4]

Phonology

Consonants

Siebert found 23 consonants in his limited research,[5] while Rankin found 26. When compared with Rankin, Siebert does not include /b/, /d/, or /ʔ/. He also puts the velar plosives and postalveolar fricatives together in a palatal column. The following chart uses Rankin's analysis.

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | voiceless | p pː | t tː | k kː | ʔ | ||

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | ||||

| glottalized | tʼ | kʼ | |||||

| voiced | b | d | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | s | ʃ | x | h | ||

| glottalized | sʼ | ʃʼ | xʼ | ||||

| voiced | z | ʒ | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Approximant | w | ||||||

Vowels

In addition to the vowels Rankin found in the below chart, Siebert included four long oral vowels /aː/, /eː/, /iː/, and /oː/.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ĩ | ||

| Mid | e | o õ | |

| Open | a ã |

Revitalization

Ardina Moore taught Quapaw language classes through the tribe.[7]

An online audio lexicon of the Quapaw language is available on the tribal website to assist language learners.[8] The lexicon incorporates audio of first language speakers who were born between 1870 and 1918.

The 2nd Annual Dhegiha Gathering in 2012 brought Quapaw, Osage, Kaw, Ponca, and Omaha speakers together to share best practices in language revitalization.[9] A Quapaw Tribal Youth Language and Cultural Preservation Camp taught the language to children.[10]

In 2024, the Quapaw Nation Culture Division created a permanent language department which hired language staff, restarted Quapaw language community classes, and is working towards increased language services. [11]

Notes

- ^ Quapaw language at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Nagle, Rebecca (November 5, 2019). "The U.S. Has spent more money erasing Native languages than saving them". High Country News. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019.

- ^ "Historical written works on the Quapaw Language". Quapaw Tribal Ancestry. Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ "Quapaw Dictionary". Quapaw Tribal Ancestry. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ Siebert, Frank T. (1989). "A Note on Quapaw". International Journal of American Linguistics. 55 (4): 471–476. doi:10.1086/466132. S2CID 143467538. Archived from the original on May 2, 2024. Retrieved May 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Rankin, Robert (1982). "A Quapaw Vocabulary". Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics. 7: 125–152. Archived from the original on December 26, 2016.

- ^ "Quapaw Language". Quapaw Tribe of Oklahoma. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ "Quapaw Language". Quapaw Tribal Ancestry. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ "Dhegiha Gathering Agenda, 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 6, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Okeson, Sarah (July 22, 2015). "Quapaw Tribe working to pass on native language". Joplin Globe. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ "Quapaw Language Department". December 27, 2024.

Further reading

- Dorsey, James Owen; La Flesche, Francis (1890). The Degiha language. Govt. Printing Office. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

External links

- Quapaw lexicon, Quapaw Tribe of Oklahoma

- Quapaw Dictionary, Quapaw Tribe of Oklahoma

- Historical works on the Quapaw Language, Quapaw Tribe of Oklahoma

- George Izard Quapaw Dictionary from 1827, Quapaw Tribe of Oklahoma

- Frank Siebert Quapaw Dictionary from 1940, Quapaw Tribe of Oklahoma

- Quapaw Indian Language (Alkansea, Arkansas, Ogahpah, Kwapa)

- Quapaw Language Reference (Google doc)

- OLAC resources in and about the Quapaw language