East Midlands English

The importance of East Midlands English in today's society is undeniable. Whether it is a particular person or topic, East Midlands English has a significant impact on our daily lives. Throughout history, East Midlands English has been the subject of debate and discussion, stirring emotions and driving change. In this article, we will explore the role East Midlands English plays in our daily lives, as well as its influence on different aspects of society. From its impact on culture to its role in politics and economics, East Midlands English has a prominent place on the world stage. Knowing more about East Midlands English allows us to better understand the world around us and the forces that shape our reality.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| East Midlands English | |

|---|---|

| Native to | England |

| Region | East Midlands |

| Ethnicity | English |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | East Midlands English |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

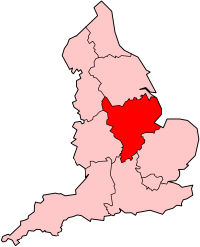

Location of The East Midlands within England | |

East Midlands English is a dialect, including local and social variations spoken in most parts of East Midlands England. It generally includes areas east of Watling Street[n 1] (which separates it from West Midlands English), north of an isogloss separating it from variants of Southern English (e.g. Oxfordshire) and East Anglian English (e.g. Cambridgeshire), and south of another separating it from Northern English dialects (e.g. Yorkshire).

This includes the counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Rutland and Northamptonshire. Dialects of the northern parts of the East Midlands usually share similarities with Northern English dialects while dialects of the southern parts have similarities with Southern England and parts of the west have some similarities with the West Midlands. Relative to other English dialects, there have been relatively few studies of East Midlands English.

Origins

The Eastern English Midlands were incorporated in the Norse-controlled Danelaw in the late 9th century by Ivar the Boneless. With their conquest, the county towns of the East Midlands counties were converted into fortified, Viking city-states, known as the Five Boroughs of the Danelaw. The region's dialect owes much of its grammar and vocabulary to the Nordic influences of its conquerors. For example, the East Midlands verb to scraight ('to cry') is thought to be derived from the Norse, skrike in modern Scandinavian, also meaning to cry.[2]

The East Midlands dialect of Middle English which extended over a much larger area, as far south as Middlesex, is the precursor of modern English spoken today,[3] which has descended from the early modern English of the early 16th century.

East Midlands dialects in literature

The novelist and East Midlander D. H. Lawrence was from the Nottinghamshire town of Eastwood and wrote in the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Coalfield dialects in several poems as well as in his more famous works such as Lady Chatterley's Lover and Sons and Lovers.[4]

Though spoken less commonly today, the dialect of the East Midlands has been investigated in texts such as the Ey Up Mi Duck[5] series of books (and an LP) by Richard Scollins and John Titford. These books were originally intended as a study of Derbyshire Dialect, particularly the distinctive speech of Ilkeston and the Erewash valley, but later editions acknowledge similarities in vocabulary and grammar which unite the East Midlands dialects and broadened their appeal to the region as a whole.

"Ey up" (often spelt ayup / eyup) is a greeting thought to be of Old Norse origin (se upp) used widely throughout the East Midlands, North Midlands, North Staffordshire and Yorkshire, and "m' duck" is thought to be derived from a respectful Anglo Saxon form of address, "Duka" (literally "duke"), and is unrelated to waterfowl.[6][n 2] Non-natives of the East Midlands and North Staffordshire are often surprised to hear men greet each other as "m' duck".

Grammar

Those who speak traditional regional dialects are not trying unsuccessfully to speak Standard English. East Midlands English follows a series of distinct grammatical rules. Some examples follow below.

Formal address

Until the mid-20th century, it was not uncommon to hear the use of informal forms of address, thee and thou, as compared to the more formal you. Use of the informal form of address is now uncommon in modern speech.

Personal and possessive pronouns

Personal pronouns differ from standard English as follows:

|

|

|

Example: It eent theirn; it's ourn! (It isn't theirs; it's ours!)

Reflexive pronouns

Reflexive pronouns are characterised by the replacement of "self" with sen (from Middle English seluen)

- Y'usen – Yourself

- Mesen – Myself

- Thisens – Themselves/Yourselves

- Ussens – Ourselves

Example: We sh'll ay to do it ussens. (We shall have to do it ourselves.)

Vocabulary

Humorous texts, such as Nottingham As it is Spoke, have used their phonetically spelled words to deliberately confuse non-natives of the region.[9]

- Alrate yooth?

- Are you alright young man? Here, ⟨alrate⟩ is a spelling designed to convey the phonological specification in the traditional dialect of ⟨right⟩, which is /riːt/, and a slight diphthonging of /iː/.

- Avya gorra wi'ya?

- Is the wife with you? (lit. "Have you got her with you?) The pronunciation /wɪ jə/ with weak form WITH is alleged to be more common in Nottingham and the South East Midlands; pronunciations with th-fronting in WITH are alleged to be more common elsewhere. TH-fronting became a potential feature of the accents of the region in around 1960.[10] The humorous spellings are designed to indicate H-dropping, the ’'Northern T-to-R rule'’ and /wi/, the non-Standard weakform of ⟨with⟩, which is common to many dialects in England.

- 'Int any onya any onya?

- Here is an example of Belper, Derbyshire dialect when asking a group of people if any of them have any matches with which to light a pipe. Hasn’t any of you, got any on you?

- It's looking' a bit black ower Bill's movver's

- It looks like rain. (lit. "It's looking a bit black over Bill's Mother's.") – a common, if somewhat old-fashioned, Midlands expression implying impending bad weather. The spelling ⟨ower⟩ chosen to indicate the phonological specification in the traditional dialect of ⟨over⟩: /ɒvɚ/. The identity of Bill or where his mother's house was located is open to question, although it is possibly derived from German emperor Wilhelm II.[11]

- Awont gooin t’worra!

- I wasn't going to, was I! ⟨Awont⟩ , ⟨gunta⟩ and ⟨worra⟩ are blend words designed to convey the phonological specification in the traditional dialect of ⟨I wasn't⟩, ⟨going to⟩ and ⟨was I⟩.

- A farnd im in cut

- I found him in the Canal, (lit. "I found him in the cut). Using the traditional and local word ⟨Cut⟩ for Canal. Canals were originally referred to as "Cuts" because during the industrial revolution canals or highways for transportation of goods were literally "cut" into the landscape and allowed to fill with water.

- Thez summat up wi’im

- I think he may be ill. (lit. "There's something up with him."). The spellings here chosen to indicate the ‘'Northern'’ feature that /eə/ is a monophthong, the non-Standard English word /ˈsʌmət/, which is historically found in many dialects across England (cf. its use by the London boatmen Gaffer and Riderhood in Our Mutual Friend and by the farmhands in Far from the Madding Crowd), the weakform of ⟨with⟩ previously mentioned and H-dropping.

- Yer norrayin no tuffees!

- You're not having any sweets! (should not be taken to mean 'toffees' alone as in East Midlands dialect' "tuffees" can mean all types of sweets). Humorous spellings here were chosen to indicate the Northern T-to-R rule and the phonological specification in the traditional dialect of ⟨have⟩, which is /eɪ/.

However, there are many words in use in the traditional East Midlands Dialect which do not appear in standard English. The short list below is by no means exhaustive. More comprehensive glossaries exist within texts such as Ey Up Mi Duck by Richard Scollins and John Titford.

- naught /nəʊt/

- nothing (homographic with /nɔːt/ the digit cypher, 0, and the (now only literary) naught /nɔːt/ of General English; /nəʊt/ is a traditional dialect phonological specification and /nɔːt/ is the regular development in General English).

- aught /əʊt/

- anything (homographic with the now literary General English /ɔːt/)

- nesh

- a weak person, or one who feels the cold. Found in many parts of England, cf. its use in Hardy.

- belt-job

- easy job (used in certain coal-mining communities based on watching a conveyor belt)

- causie

- pavement ("causey" is an older word from which 'causeway' is derived.[12])

- cob

- a bread roll (bap); (as verb) to throw

- cob loaf

- baker's term used across the UK for a hemispherical loaf

- clouts

- trousers (/klaʊts/, usually pronounced ); (as verb:) hits something or someone.

- jitty/jetty

- alleyway.

- twitchel

- alleyway. Typically (but not exclusively) alleyways providing access to the rear of terraced housing. Can also mean a path between gardens (E.g. allotments)

- larup/larop

- to cover with (usually a thick substance)

- mardy (or etymological marredy)

- grumpy, sulky (i.e. "She's a mardy one!")

- mash

- to make a pot of tea (i.e. "I'll go n’mash tea.")

- piggle

- to pick at a scab, spot or a skin irritation (i.e. "Stop piggling that scab!")

- puddled/puddle-drunk

- intoxicated or stupid

- puther

- to pour out uncontrollably[13] usually of smoke, steam or dust

- rammel

- rubbish/waste

- scraight/scraitin'

- to cry/crying[4]

- sile

- rain heavily

- snapin or snap

- lunch/food,tekken ta werk[14]

- snidered/snided/snied

- covered/infested, (DH Lawrence used the word 'Snied' in a description of an infestation of mice in Sons and Lovers.),[14]

- wazzerk/wassock

- fool (used across the East & West Midlands)

There are also word forms that occur in Standard English but which have additional meanings in some of the varieties considered here.

- bonny

- In many dialects, this has the sense of 'looking well' often referring to a healthy plumpness.[15][16] In Derby, Leicester and Nottingham, there still also exists a transferred sense of plump, robust, stout or overweight derived from this sense. Cf. Samuel Johnson's comment that ‘'It seems to be used in general conversation for plump’’ as cited in NED Bonny 2 b as (J.).

(There is a yet older sense now only commonly used in Scots, Northern & some Midland dialects meaning 'beautiful' generally rather than of individuals having a pleasing embonpoint specifically.)[17]

- fast

- stuck, caught (i.e. "Who's got a finger fast?")

- tuffees

- sweets, confectionery

- badly

- hungover/ill

- croaker

- doctor

- croggie

- an (illegal) crossbar ride, "two-up" on the crossbar of a bicycle

- duck's necks

- bottle of lemonade

- fuddle

- an ad hoc buffet or Potluck

- oakie

- ice cream (common in Leicestershire) see Hokey cokey

- pot

- a plaster cast

- sucker

- iced lolly

- tabs

- ears, also called lugholes

- yack

- to yank

- cos

- can you

The greeting 'now then' (as 'Nah theen') is still in use in Lincolnshire and North-East Derbyshire, used where other people might say "Hello".[citation needed] 'Nen mate' can also be heard instead of "now then mate".

People from Leicester are known in the popular holiday resort Skegness as "Chits", due to their expression for "how much is it" when asking the price of goods in shops.[18]

Phonology

- East Midlands accents generally lack the trap–bath split, so that cast is pronounced rather than the pronunciation associated with most southern accents. The Northampton accent has lengthening .

- Most accents in the East Midlands lack the foot–strut split, with words containing /ʌ/ like strut or but being pronounced with , without any distinction between putt and put.

- East Midlands accents are generally non-rhotic.

- The PRICE vowel has a very far back starting-point, and can be realised as .[19]

- Yod-dropping, as in East Anglia, can be found in some areas[where?], for example new as /nuː/, sounding like "noo".

- H-dropping is common, in which is usually omitted from most words,[20] while NG-coalescence is present in most of the East Midlands except in Derbyshire where is pronounced as .[21]

- In Lincolnshire, sounds like the u vowel of words like strut being realised as may be even shorter than in the North.

- In Leicester, words with short vowels such as up and last have a northern pronunciation, whereas words with vowels such as down and road sound rather more like a south-eastern accent. The vowel sound at the end of words like border (and the name of the city) is also a distinctive feature.[22]

- Lincolnshire also has a marked north–south split in terms of accent. The north shares many features with Yorkshire, such as the open a sound in "car" and "park" or the replacement of take, make, and sake with tek, mek, and sek.[23] The south of Lincolnshire is close to Received Pronunciation, although it still has a short Northern a in words such as bath.

- Mixing of the words was and were when the other is used in Standard English.

- In Northamptonshire, crossed by the north–south isogloss, residents of the north of the county have an accent similar to that of Leicestershire and those in the south an accent similar to rural Oxfordshire.

- The town of Corby in northern Northamptonshire has an accent with some originally Scottish features, apparently due to immigration of Scottish steelworkers.[24] It is common in Corby for the GOAT set of words to be pronounced with /oː/. This pronunciation is used across Scotland and most of Northern England, but Corby is alone in the Midlands in using it.[25]

Dialect variations within the political region

Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire is in the East Midlands region defined in the late 20th century, and has historically harboured its own dialect comparable to other forms of East Midlands English,[13] particularly among the older generation. However, more recently its linguistic distinctiveness has significantly eroded due to influences from the western parts of East Anglia, the West Midlands, and the South as well as the 'Watford Gap isogloss', the demarcation line between southern and northern English accents.

The Danelaw split the present county into a Viking north and a Saxon south. This is quite plainly heard, with people in the south speaking more like people from Oxfordshire or Cambridgeshire and people in the north sounding more like people from Leicestershire.[citation needed]

Corbyite

Also of note is the anomalous dialect of Corbyite spoken around Corby, Kettering, and Market Harborough in the north of Northamptonshire and the south east of Leicestershire, which reflects the migration of large numbers of Scottish and Irish steelworkers to the town during the 20th century. The dialect is often compared to Glaswegian.[citation needed]

Derbyshire

Derbyshire, unlike other counties in the East Midlands, has many different accents and dialects within its boundaries. This is in part due to its borders taking in areas that are naturally "cut off" from the rest of the county by topographical borders such as that of the Peak District, as well as areas that are of considerable distance from the city of Derby and its diaspora, therefore being too far away to be of any influence both linguistically and culturally. This means that dialects in other parts of Derbyshire have more influence from neighbouring counties and cities, especially with the northern parts of the county lying in close proximity to both North West England and Yorkshire.

The city of Derby, as well as boroughs in the vicinity of the city such as Amber Valley and Erewash, share a common Derby dialect, which sounds largely similar to other East Midlands cities and counties. In addition, the town of Burton upon Trent, in Staffordshire, has an accent that is more identifiable as an East Midlands accent. This is largely due to the town's location near the borders with Derbyshire and Leicestershire, as well as the A38 providing commuter links to and from the East Midlands.

However, as previously mentioned, many other areas within the boundaries of Derbyshire have accents influenced by neighbouring counties and cities. For example, the dialect of Glossop, Hadfield and Gamesley in the Borough of High Peak is largely similar to the Manchester dialect due to being less than a mile in places from the border with Greater Manchester; while that of the Hope Valley, North East Derbyshire, Chesterfield and Bolsover share commonalities with the South Yorkshire dialect owing to their proximity to Sheffield. In addition, the dialect of Buxton and parts of the Derbyshire Dales echoes that of the nearby areas of Stoke-on-Trent, East Cheshire and the Staffordshire Moorlands.

The dialect of Coalville in Leicestershire is said to resemble that of Derby because many of the Coalville miners came from there. Coalville's name is still almost exclusive pronounced as "Co-ville" by its inhabitants. Neighbouring pit villages such as Whitwick ("Whittick") share the Coalville inflection as a result of the same huge influx of Derbyshire miners.

Lincolnshire and East Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire has long been an economically relatively homogeneous, less industrial more heavily agricultural county and is in part naturally separated by the River Trent divorcing its largest market town, Gainsborough, Torksey and the City of Lincoln from Nottinghamshire. East of the Lincolnshire Wolds, in the southern part of the county, the Lincolnshire dialect is closely linked to The Fens and East Anglia where East Anglian English is spoken, and, in the northern areas of the county, the local speech has characteristics in common with the speech of the East Riding of Yorkshire. This is largely due to the fact that the majority of the land area of Lincolnshire was surrounded by sea, the Humber, marshland, and the Wolds; these geographical circumstances permitted little linguistic interference from the East Midlands dialects until the nineteenth century when canal and rail routes penetrated the eastern heartland of the country.

Nottinghamshire

Minor variations still endure between Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. Though all native speakers sound similar, there are noticeable differences between the accents of residents of, for example, Nottingham and Derby[citation needed], or Mansfield and Bolsover which is pronounced locally as /boʊzə/.[citation needed]

The dialect of Bassetlaw in north Nottinghamshire, is very similar to South Yorkshire due to its proximity to both Sheffield and Doncaster. This includes the occasional use of the pronoun thou amongst older people. Examples of speech in the Worksop area is shown in Stephen Whyles's book A Scab is no Son of Mine .[citation needed]

Counties in which East Midlands English is spoken

- Cambridgeshire (Limited usage around Peterborough)

- Derbyshire (Limited usage in northern areas such as High Peak, Chesterfield and Bolsover)

- Leicestershire

- Lincolnshire (except areas within the Yorkshire and the Humber region)

- Nottinghamshire (Usage less frequent in Bassetlaw)

- Northamptonshire

- Rutland

- Staffordshire (Limited usage around Burton-upon-Trent and Uttoxeter)

In popular culture

The children's writer Helen Cresswell came from Nottingham, lived in Eakring and some of her characters featured on television during the 1970s and 1980s, such as Lizzie Dripping and Polly Flint, have distinct East Midlands accents, otherwise rarely heard in national broadcast media at the time.[citation needed]

Actor Jack O'Connell has a distinct Derbyshire accent.

The character 'Sylvie' in the Disney+ Marvel series 'Loki', played by Sophia Di Martino, has an East Midlands accent: "Di Martino's desire to represent underserved people led her to use her natural Nottingham accent on 'Loki'.[26]

Notes

- ^ Also termed the A5 or London – Shrewsbury road

- ^ There are also other suggestions for the origin of the term 'duck': one being attributed to a group of young children who would congregate in the River Derwent in the Morledge area of Derby in the early 19th century, a time when the flow of the river was much slower. People who watched them sometimes remarked that they could "swim like ducks", an observation Joseph Masters once remarked in his memoirs. The children soon greeted each other with 'Ey up, my duck', calling themselves the 'Derby ducks' not long thereafter.[7] This story has to be scrutinized against the word duck having been a term of endearment since at least the 1580s.[8]

References

- ^ Falkus & Gillingham and Hill.

- ^ "BBC Inside Out – Dialect". BBC. 17 January 2005. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ "East Midland Dialect". Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford University Press. January 2003. ISBN 9780192800619.

- ^ a b Pavel, John (23 April 2008). "Dialect poems by D.H. Lawrence". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Scollins, Richard; Titford, John (1 September 2000). Ey Up Mi Duck!. Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-85306-658-0.

- ^ "History of the Potteries dialect". BBC. 2005. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ "Opinion: 'A quacking definition of Derby famous 'mi duck' greeting'". Derby Telegraph. 29 March 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Duck". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "Books". The Old Meadows.co.uk. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Kerswill, Paul (2003). "Dialect levelling and geographical diffusion in British English". In Britain, D.; Cheshire, J. (eds.). Social Dialectology. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 223–243 – via Researchgate.net.

- ^ Meierhans, Jennifer (6 November 2016). "England's oddest phrases explained". BBC News.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 558.

- ^ a b "Local Dialect Words and Usage". Sulgrave.org. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Sons and Lovers". Archived from the original on 30 June 2007.

- ^ A New English Dictionary (1888) Bonny, adj., 2. b. (https://archive.org/stream/oed01arch#page/987/mode/1up)

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary 2nd ed. (1989) Bonny, adj., 2. b.

- ^ A New English Dictionary (1888) 2nd Bonny, adj., 1. (https://archive.org/stream/oed01arch#page/987/mode/1up)

- ^ Leicester Mercury, 16 July 2004

- ^ Hughes, Trudgill & Watts ed., English accents and dialects: an introduction to social and regional varieties of English in the British Isles, chapter on Leicester's speech, Hodder Arnold, 2005

- ^ Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2002). The Phonetics of Dutch and English (5 ed.). Leiden/Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 290–302.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 189, 366.

- ^ "Voices – The Voices Recordings". BBC. 6 July 1975. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ Stoddart, Jana; Upton, Clive; Widdowson, J.D.A. (1999). "Sheffield dialect in the 1990s: revisiting the concept of NORMs". Urban Voices. London: Arnold. p. 74.

- ^ https://archive.today/20240524044851/https://www.webcitation.org/5QdQDYjD0?url=http://www.joensuu.fi/fld/methodsxi/abstracts/dyer.html. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Language in the British Isles, page 67, ed. David Britain, Cambridge University Press, 2007

- ^ Clough, Rob (15 September 2021). "The Untold Truth of Sophia Di Martino". Looper.com. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

Bibliography

- Evans, Arthur Benoni (1881) Leicestershire Words, Phrases and Sayings; ed. by Sebastian Evans. London: Trübner for the English Dialect Society

- Wright, Joseph (ed.) (1898–1905) The English Dialect Dictionary. 6 vols. Oxford University Press ("appendices include dialect words grouped by region")

- Skeat, W. W. (ed.) (1874) "Derbyshire lead mining terms", by T. Houghton; 1681 ... "Derbyshire mining terms", by J. Mawe; 1802 . London: N. Trübner for the English Dialect Society

- Mander, James (1824) The Derbyshire Miners' Glossary. Bakewell : Printed at the Minerva Press, for the author by G. Nall (High Peak and Wirksworth districts)

- Pegge, Samuel (1896) Two Collections of Derbicisms; ed. by W. W. Skeat & T. Hallam. London: for the English Dialect Society by H. Frowde, Oxford University Press

- Braber, N. (2014). 'The concept of identity in the East Midlands'. English Today 30: 3–10.

External links

- Far-welter'd: the East Lincolnshire Dialect Society

- Dialect words recorded in the Northamptonshire village of Sulgrave

- Specimens of the Coalville dialect

- Conversation in Coalville about accent, dialect and attitudes to language; BBC Voices; British Library

- BBC information page on E. Midlands Dialect

- Angelina Jolie baffles Holywood with 'ay up mi duck'

- Dolly Parton says 'ay up mi duck' at book scheme launch

- Dialect Poems from the English regions