Mandombe script

| Mandombe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | Featural alphabet |

| Creator | Wabeladio Payi |

| Time period | 1978–present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Kikongo, Kikongo ya leta, Lingala, Tshiluba, Swahili |

| Related scripts | |

| Parent systems | Artificial script

|

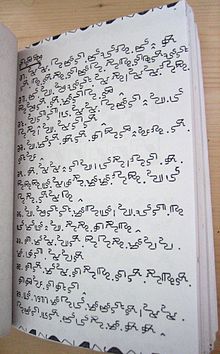

A Mandombe book

A Mandombe book

Mandombe or Mandombé is a script proposed in 1978 in Mbanza-Ngungu in the Bas-Congo province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Wabeladio Payi, who related that it was revealed to him in a dream by Simon Kimbangu, the prophet of the Kimbanguist Church. Mandombe is based on the sacred shapes ![]() and

and ![]() , and intended for writing African languages such as Kikongo, as well as the four national languages of the Congo, Kikongo ya leta, Lingala, Tshiluba and Swahili, though it does not have enough vowels to write Lingala fully. It is taught in Kimbanguist church schools in Angola, the Republic of the Congo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is also promoted by the Kimbanguist Centre de l’Écriture Négro-Africaine (CENA). The Mandombe Academy at CENA is currently working on transcribing other African languages in the script. It has been classified as the third most viable indigenous script of recent indigenous west African scripts, behind only the Vai syllabary and the N'Ko alphabet.

, and intended for writing African languages such as Kikongo, as well as the four national languages of the Congo, Kikongo ya leta, Lingala, Tshiluba and Swahili, though it does not have enough vowels to write Lingala fully. It is taught in Kimbanguist church schools in Angola, the Republic of the Congo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is also promoted by the Kimbanguist Centre de l’Écriture Négro-Africaine (CENA). The Mandombe Academy at CENA is currently working on transcribing other African languages in the script. It has been classified as the third most viable indigenous script of recent indigenous west African scripts, behind only the Vai syllabary and the N'Ko alphabet.

A preliminary proposal has been made to include this script in the combined character encoding ISO 10646/Unicode. A revised Unicode proposal was written in February 2016 by Andrij Rovenchak, Helma Pasch, Charles Riley, and Nandefo Robert Wazi.

Structure

Mandombe has consonant letters and vowel letters which are combined into syllabic blocks, rather like hangul. All letters are based on a square S or 5 shape. The six vowels are distinguished by numerals added to the right of the 5-shape. The consonants fall into four 'groups', or shapes, which are distinguished by adding a short stroke to the 5-shape for three of the groups; and into four 'families', or orientations, which are distinguished by reflecting and rotating the letter shapes. The four families of consonants are attached to the same corner of the vowel, which is reflected or rotated to match the consonant, so that the consonant resides in a different corner of the syllabic block depending on its orientation. Unlike Pitman shorthand, which also distinguishes consonants by rotation, in Mandombe the groups and families do not form natural classes, apart from a fifth group of fricatives and affricates made by inverting one of the four basic groups. Vowel sequences and nasal vowels are created with diacritics, prenasalized consonants by prefixing n (the basic 5-shape), and consonant clusters by inserting a consonant between the two parts of the vowel (between the 5-shape and the additional strokes).

Vowels

Vowel letters are composed of two parts: the basic 5-shape of the Mandombe script plus a numeral, or—in the case of ü (/y/)—by modifying the basic u vowel letter. Vowel 1 is i, vowel 2 u, vowel 3 e, vowel 4 o, and vowel 5 a.

A vowel can be written individually and form a syllable on its own. In a vowel sequence or diphthong, however, a diacritic is used for the second vowel or part of the vowel. That is, lio (two syllables) is written li plus the diacritic for o, while mwa (one syllable) is written mu plus the diacritic for a. Diacritics come at the end of the last stroke of the vowel. While there is a diacritic for u, sequences ending in u are instead generally written as two full syllables, the second being wu. This strategy is apparently also employed in some other cases rather than using diacritics.

| Latin script | Mandombe | Composition | Diacritic |

|---|---|---|---|

| i | |||

| u | ? | ||

| e | |||

| o | |||

| a |

Consonants groups and families

There are four basic consonant shapes. Each shape (base character) can be reflected horizontally, vertically, or both to represent a different consonant; the four consonants thus formed are considered to be a group, and consonants reflected in the same way are considered to be a family. These consonants are combined with vowels, which are similarly reflected, to create syllables.

Family 1 The consonant with the basic orientation is attached to the lower left of the vowel Family 2 The consonant-plus-vowel is reflected both horizontally and vertically (rotated 180°) Family 3 The consonant-plus-vowel is reflected horizontally Family 4 The consonant-plus-vowel is reflected verticallyVowel diacritics are reflected along with the main vowel.

The use of geometric transformation is also present in Pitman shorthand and Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics, though Mandombe consonants in the same group do not seem to have any phonological relationship (except the fifth group named mazita ma zindinga, in which all consonants are affricates and fricatives).

Examples

| Consonant | Family 1 | Family 2 | Family 3 | Family 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Group 1 |

na |

va |

sa |

ta |

Group 2 |

be |

de |

fe |

ge |

Group 3 |

ko |

mo |

lo |

po |

Group 4 |

wi |

ri |

zi |

yi |

| Mazita ma zindinga | shu |

dju |

tshu |

ju |

Complex characters

- Prenasalisation of consonants is indicated with a variation on

(n) disconnected from the vowel. This always joins the consonant body, else certain signs could be read in more than one way.

(n) disconnected from the vowel. This always joins the consonant body, else certain signs could be read in more than one way. - Nasalisation of the vowel is marked by an attached diacritic:

.

. - If

is placed between the two separable parts of the vowel glyph, it represents an intervening /r/.

is placed between the two separable parts of the vowel glyph, it represents an intervening /r/.

Examples of complex syllables

| Modification | Mandombe | Latin script |

|---|---|---|

| Vowel sequence | bie | |

| Diphthong/semivowel | mwa | |

| Nasal vowel or final nasal consonant | ken | |

| Prenasalized consonant | mbu | |

| Labial occlusion | gba | |

| Consonant clusters | pro | |

| plo |

Tones

| High tone | pó |

Digits

The digit for 1 resembles the Arabic numeral 1, and 2–5 are based on this shape. 6 and 9 are square versions of Arabic 6 and 9, and 7–8 are formed by reflecting them.

1–5 are also the shapes used for the vowels i u e o a.

| digit | Mandombe |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 |

Punctuation

A period is used as a word divider to separate words.

The punctuation corresponds to that of the Roman alphabet. A comma has the form of a short line, ![]() , a period a turned vee,

, a period a turned vee, ![]() , like the diacritic for o, and a colon and semicolon combinations of these (semicolon î, colon double

, like the diacritic for o, and a colon and semicolon combinations of these (semicolon î, colon double ![]() ). The exclamation mark is like a lambda, λ, and the question mark is like a turned Y, ⅄.

). The exclamation mark is like a lambda, λ, and the question mark is like a turned Y, ⅄.

See also

External links

- L'écriture Mandombe (in French)

- Mandombe script

- Pasch describing the script, its origins, and its uses

References

- ^ Pasch, Helma. 2008. Competing scripts: the introduction of the Roman alphabet in Africa. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 191:65–109.

- ^ Unseth, Peter. 2011. Invention of Scripts in West Africa for Ethnic Revitalization. In The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts, ed. by Joshua A. Fishman and Ofelia García, pp. 23–32. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Rovenchak, Andrij; Pasch, Helma; Riley, Charles; Wazi, Nandefo Robert (20 July 2015). "Preliminary proposal for encoding the Mandombe script in the SMP of the UCS Revised)" (PDF). Unicode. Retrieved 30 July 2015.