Isaiah 58

In today's article we are going to explore Isaiah 58, a topic that has sparked the interest of many people over time. Isaiah 58 is a relevant aspect in today's society, since it affects different areas of daily life. Throughout this article we will examine various perspectives on Isaiah 58, as well as its impact today. Furthermore, we will explore different approaches and opinions that have emerged around this topic, with the aim of providing a complete and enriching view of Isaiah 58. Don't miss this interesting exploration of Isaiah 58!

| Isaiah 58 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Book | Book of Isaiah |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 5 |

| Category | Latter Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 23 |

Isaiah 58 is the fifty-eighth chapter of the Book of Isaiah in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. This book contains the prophecies attributed to the prophet Isaiah, and is one of the Books of the Prophets. Chapters 56-66 are often referred to as Trito-Isaiah.[1] This chapter contains a proclamation regarding "fasting that pleases God".[2]

Text

The original text was written in Hebrew language. This chapter is divided into 14 verses.

Textual witnesses

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), the Petersburg Codex of the Prophets (916), Aleppo Codex (10th century), Codex Leningradensis (1008).[3]

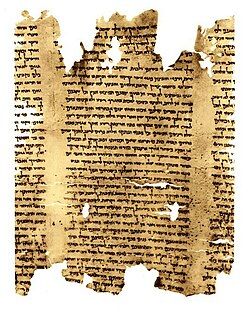

Fragments containing parts of this chapter were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls (3rd century BCE or later):

- 1QIsaa: with all verses (1–14)

- 1QIsab with all verses (1–14)

- 4QIsad (4Q58): extant verses 1–3, 5–7

- 4QIsan (4Q67): extant verses 13–14

There is also a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint, made in the last few centuries BCE. Extant ancient manuscripts of the Septuagint version include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century), Codex Sinaiticus (S; BHK: S; 4th century), Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century) and Codex Marchalianus (Q; Q; 6th century).[4]

Parashot

The parashah sections listed here are based on the Aleppo Codex.[5] Isaiah 58 is a part of the Consolations (Isaiah 40–66). {P}: open parashah.

- {P} 58:1-14 {P}

Verse 3

- Wherefore have we fasted, say they, and thou seest not?

- wherefore have we afflicted our soul, and thou takest no knowledge?

- Behold, in the day of your fast ye find pleasure,

- and exact all your labours.[6]

Verse 12

- And they that shall be of thee shall build the old waste places:

- thou shalt raise up the foundations of many generations;

- and thou shalt be called, The repairer of the breach,

- The restorer of paths to dwell in.[7]

In some versions, "the old waste places" is translated as "ancient ruins": John Skinner, in the Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges, suggests that "the description of the ruins as 'ancient' suggests a period considerably later than the Exile (which only lasted half a century), although the argument is not one that can be rigorously pressed".[8]

See also

References

- ^ Oxford Reference, Overview: Bernhard Duhm accessed 6 September 2018

- ^ Sub-title to Isaiah 58:1–14 in the New King James Version

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 73–74.

- ^ As implemented in the Jewish Publication Society's 1917 edition of the Hebrew Bible in English.

- ^ Isaiah 58:3

- ^ Isaiah 58:12

- ^ Skinner, J., Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges on Isaiah 58, accessed 10 September 2018

Bibliography

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.